Chicago Daily Law Bulletin: Mock Trial, Real Lessons - Midtown Center Inaugural Law Apprenticeship

Mock trial, real lessons

By Roy Strom, Law Bulletin staff writer

Published in the Chicago Daily Law Bulletin on August 12, 2013.

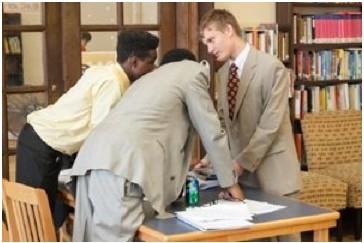

Ben Speckmann

(From left to right) Student Patrick Elliott cross-examines classmate Luis Guerrero, playing the role of a fraternity member accused of first-degree murder, as adviser Geoffery Burdell, teacher Zachary Reeder and second assistant Lucas Williams act as judges during a mock trial at the Midtown Center, 1819 N. Wood St., on Thursday. The mock trial resulted from a six-week class sponsored by Winston & Strawn LLP that taught 15 students legal basics and provided a $400 stipend for good behavior.

A witness had just lied, and defense lawyer Eugene Murawski knew exactly what he wanted to do — impeach him and get the statement stricken from the record.

“Of course, as bad luck would have it, I forgot how to impeach,” Murawski said.

Although that mistake led to his client being convicted of first-degree murder and criminal hazing, Murawski will not be facing a malpractice suit — only mild taunting from his classmates.

A soon-to-be sophomore at Saint Patrick High School, Murawski’s slipup on Thursday came during a mock trial that was the culmination of a six-week class that taught 15 high school boys the basics about the law and life as a lawyer.

Through a Winston & Strawn LLP-sponsored apprenticeship program at the Midtown Center, the students visited a downtown law firm, a judge’s chambers and a jail, in addition to learning how to put on a trial — a skill they displayed last week during three hours of opening statements, witness testimony fraught with objections and closing arguments.

“The goal isn’t to teach them everything you need to know to be a lawyer,” said Zachary Reeder, a Florida-licensed lawyer who moved to Chicago last year and taught the class.

“It’s to be able to actually consider things … and try to realize that there’s always two sides to an argument, not to rush to judgment on things.”

Many of them cloaked in oversized suits, the dapper student-lawyers argued a case in which a fraternity member was charged with first-degree murder and criminal hazing.

Ben Speckmann

Eugene Murawski (right) consults fellow “defense lawyers” Andrew Taylor (left) and Quinton Karamoko during a mock trial Thursday. The event was the culmination of a six-week class sponsored by Winston & Strawn LLP to teach legal basics to 15 students at the Midtown Center.

A hopeful sorority member — painted by defense lawyers as a “perfectionist” eager to fit in — had died after she fell off a university clock tower.

The fall was either a rite of passage gone awry or the work of a cruel murderer played by student Luis Guerrero, whom the prosecution portrayed as a callous “back-stabber.”

While they at times struggled with courtroom procedure, the students took the roles seriously — Murawski’s team jotted notes on an iPad while the prosecution excitedly whispered tactics. They had good reason, as the class paid a $400 stipend to the students that could be docked for bad behavior.

The trial’s pivotal moment, jurors would say later, came when the closest thing the prosecution had to an eyewitness was cross-examined by Murawski.

The heart of the fictional case was whether Guerrero’s character pushed the sorority woman off a bell tower, or whether the young woman, who had a blood alcohol content of .10, fell to an accidental death.

In his deposition, one of the friends of Guerrero’s character had testified to being inside the bell tower, though not present to see how the woman died.

But the witness — who stood to become the fraternity’s president if Guerrero’s character was jailed — changed his story on the stand, saying he saw a push.

Murawski sprung into what he thought was an impeachment.

Upon being told by the judge, played by Reeder, that he had skipped a step in the impeachment process, Murawski asked, “If you forgot how to do an impeachment, then that’s too bad?”

A nod of the judge’s head sealed Guerrero’s character’s fate as guilty on both counts.

“The prosecution got some stuff in that I think the defense should not have let in, like (the witness) saying he saw (a push). He never did. But the defense let that in and the jury would never know the difference,” said Jeffrey Burrel, an adviser for the class who acted as the decisive juror.

While he said both sides were good students who put in a lot of effort, someone had to lose.

“I don’t think the defense developed the other stories for why she would have jumped or why she would have fallen,” Burrel said.

Patrick Elliott, a soon-to-be junior at the Latin School of Chicago who played the role of prosecutor, said he was “extremely happy” as he enjoyed a candy bar his three-lawyer, three-witness team received for winning.

“We felt we had a really strong case,” Elliott said. “In the beginning we thought we were going to lose, but we started just working harder and we ended up winning.”

After the verdict, Sam Ocon — who has known Murawski since the first grade and gave the prosecution’s closing argument — briefly reveled in his friend’s defeat.

Murawski, who insists he’s serious when he says his life goal is to become president of the United States, waved his friend away and said, “It hurts.”

“His lawyer license should be revoked because he blatantly lied to the court,” he said. “It’s the reason we lost. Because he blatantly lied to the court and he got away with it.”

While the mock trial made for good theater, it was only a portion of the summer class.

In addition to keeping these high school students busy during what can be a turbulent time in some of the neighborhoods where they live, it also helped foment an interest in the law, students and teachers said.

“I love combating and critical thinking,” said Elliott, who pulled off four consecutive impeachments of Guerrero’s character, which led judges to allow him to skip some specific steps that tripped up his opponent.

“I’m a junior this year, so it’s definitely a profession I’m looking to consider. I don’t know yet, but it’s either that or maybe being an engineer.”

Michael Y. Scudder — a partner at Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP — hosted the students this summer at his firm’s downtown office, where they argued a historic Supreme Court case that originated on the streets of Chicago and centered on lawful stop-and-searches.

“What I really wanted to impart to them is that there are multiple perspectives from which to approach difficult questions,” Scudder said.

“And it’s important in coming to your own answer to a question to make sure that you’re considering and accounting for those multiple perspectives.”

Reeder, the class teacher, said discussions around the Fourth Amendment and interactions with police officers kept the students’ attention the most.

“A lot of them before they came in seemed to have a distrust for officers,” Reeder said. “Maybe from neighborhoods they came from ... so I think that aspect, the criminal side was really interesting for them.”

Michael T. Mullins, a Winston & Strawn partner and board member at Midtown, said he hopes the program will grow next year.

“It’s good for their confidence and their analytical skill set to be able to fashion arguments and research issues and come up with a theory,” he said.

“And that’s good just generally for their skill set to move onto college.”

Asked if he would attend the program next year if he knew he would again lose the mock trial, Murawski said he would not.

What about if he won?

“Then yeah,” he said. “Winning is sort of everything.”